I hope you enjoyed reading about Lois Weber last week as much as I enjoyed writing about her. One of the most enjoyable things about this series is that I get to exploit the blog medium as much as possible in the relaying of these women’s profiles. As much as I loved graduate school, I felt that there was a serious disconnect in the way in which we conveyed our academic work.

I believe that, in this day and age, when we have access to moving image elements that can make our arguments more dynamic than ever and give further validation to our academic research, we should enrich these pieces, not leave them dry. Using stills, clips and documents within a piece is a glorious way to make a piece more palatable and, indeed, more accessible to a larger audience. Multimedia academics is a delicate world but something that is fun and wonderful to explore and intelligently exploit as often as possible. I feel that it aids the consumption of materials as much as it does the production.

So now…………

Common Careers#2: Annie Winifred Ellerman aka Bryher

Bryher, 1894-1983

Bryher is one of the most fascinating women that you have likely never heard about but you will be absolutely floored by once you have. I know I was. Born Annie Winifred Ellerman in 1894 to John Ellerman who, at the time, was the richest Brit who had ever lived, little Winifred missed out on her complete inheritance due to the fact that she was technically illegitimate: she was born 15 years before her parents were legally wed. Not to say that she wasn’t well-off she did fine, apparently showing more business sense later in life than her brother who had inherited more of the family bankroll and mismanaged it entirely. Winifred Ellerman, born of shipping royalty, was not a woman who was going to go the way of most women of the day. In fact, she went with women of the day instead.

Although she got married twice, Winifred had no questions about her sexuality: she was an out lesbian (or as out as you could be in the early part of the twentieth century), and used her husbands as “beards.” She explored that aspect of her life to the fullest, having very extensive relationships with other women, most significantly with the poetess and writer, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), who she maintained a strong relationship with from 1918 until H.D.’s death in 1961.

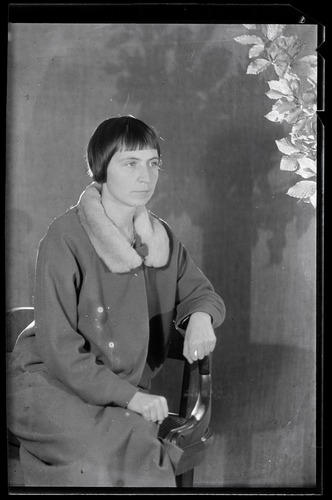

Photograph of Bryher, taken by Man Ray in 1923

According to the Cambridge Companion to Gay and Lesbian Writing, Winifred had her name legally changed by deed poll to Bryher in 1951. However, she began using it far before. The name itself was born from a fond experience of the Isles of Scilly during her youth and a desire to free herself from the bonds and obligations of what it meant to “be an Ellerman.” Thusly she renamed herself after a favored island. This would be the name she would be known by for the remainder of her writing career as well as everything else she participated in. Her solid financial status gave her the ability to back and publish a slew of different publications and fund the burgeoning psychoanalytic community in Vienna, including becoming friendly with Freud.

Not only that, but Bryher risked her very life by making her home in Switzerland a way station for Jewish refugees to escape from Germany into Switzerland, from 1933 to 1939. Indeed, without this “underground path,” one of the more notable philosophers of our time, Walter Benjamin, might have perished. Shortly after this dangerous mission, she and H.D. fled their Switzerland home to London, narrowly escaping.

Bryher married two men. She did this primarily in order to gain the freedoms that only a married woman had at the time: travel, personal independence, and complete separation from her family. Her first marriage, to Robert McAlmon, lasted from 1921-27, at which point Bryher divorced him. Mind you, she had met H.D. already, and was in a very deep relationship with her, so McAlmon also simply served as a marriage of convenience. A very short time after that first divorce, Bryher remarried Kenneth Macpherson, and they built a house in Switzerland that they called “KerWin” (after each of their names). Their marriage spanned from 1927-1947.

Neither of Bryher’s marriages was straight-up, so to speak. McAlmon was gay, thus Bryher was as much a “cover” for him as he for her. Macpherson on the other hand? Well, his relationship with Bryher was more complex and interesting. Macpherson too shared Bryher’s attraction towards the same-sex, but, on occasion, he took a female lover. At the time of his marriage to Bryher, that female lover happened to be H.D., Bryher’s lover as well. So, as you see, this was not exactly Leave it to Beaver.

Kenneth McPherson and H.D. in Switzerland, where they spent the majority of the 20s and 30s

Bryher’s confident lesbian identity never conflicted with H.D.’s bisexuality, as both women had laid claim to their sexuality early in life. Previously, H.D. even bore a daughter named Perdita (to a friend of D.H. Lawrence’s, Cecil Grey!) who Bryher ended up adopting a few years later. Contrary to the way that society at the time viewed the “homosexual impulse,” neither woman harbored any kind of negative feelings about the way that they lived their lives; these were revolutionary figures in the way that they constructed their creative and sexual identities in a world that was (and still is) very confused in the way women are allowed to do so. H.D. and Bryher had an open relationship with one another, a productive friendship and their academic/film/literary work made a significant difference in women’s history and cultural history in general.

During her marriage to McAlmon, Bryher strongly endorsed (and financially backed) his formation of the publishing company that distributed the works of authors such as Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, and Ezra Pound. After their marriage ended, she decided she did not wish to be out of the literary game and kept money flowing to Mr. Joyce and assisted American expatriate Sylvia Beach in her efforts to keep the Shakespeare and Company bookshop afloat. In 1927, shortly after getting married for the second time and beginning her cooperative relationship with Macpherson and H.D., she began to invest a great deal of time, money and energy in film-related projects. Bryher became a kind of film activist, highly involved in publishing for, creating and analyzing the cinematic world; her contributions creating a small but significant set of visual and written works that remain useful and groundbreaking even today. It was at this point that Bryher, H.D. and Macpherson began to call themselves “The POOL Group,” and proceeded to create a film company (POOL Productions), invent the first English-language journal dedicated entirely to film theory (Close-Up), and published a variety of books written by Macpherson and Bryher, as well as other film-related literature.

The POOL Group Logo

Before they began publishing or creating, POOL placed an announcement in various magazines and journals. It stated,

“POOL

is announced.

It has projects. It will mean, concerning books, new hope.

It has projects. It will mean, concerning cinematography, new beginning.

New always. Distinguished, and with a clear course.

BOOKS. FILMS.

…encouragement.

CLOSE UP a monthly magazine to begin battle for film art. Beginning July. The first periodical to approach films from any angle but the commonplace. To encourage experimental workers and amateurs. Will keep in touch with every country and watch everything. Contributions on Japanese, Negro viewpoints and problems, etc. Some of the most interesting personages of the day will write.” (p. 9, Close Up 1927-1933: Cinema and Modernism, Edited by James Donald, Anne Friedberg, & Laura Marcus)

Clearly they had quite lofty goals. Is it possible that they believed that they would keep in touch with every country and watch everything? Perhaps. The contributors to Close Up and the POOL Group themselves were very optimistic and extremely passionate as certain artists and film theorists have been known to be, (see: Cahiers du Cinema for further reference). As time wore on, however, it became very clear that the greatest accomplishment of The POOL Group was to be Close-Up, so they phased out or lessened other publications and projects and focused on that.

The film work done by the POOL Group is highly worth recognizing, however. Borderline, the experimental silent film that stars Paul Robeson and his wife as well as other POOL Group members was unavailable for years, locked away and unavailable for public consumption. But it is a masterpiece. This work not only tackles interracial romance in 1930 but was accomplished through Robeson donating much of his time almost voluntarily. Borderline ended up highly censored and controversial, as one might imagine, given the subject matter and time period. It was the POOL Group’s primary feature film, and although it was written and directed by Kenneth Macpherson, it certainly was a POOL Group production and involved all members. Much like the Lois Weber work, we must be grateful for Borderline’s recovery out of invisibility and restoration by George Eastman House, making this critically important piece of cinema once again viewable.

Bryher and H.D. filming Borderline (1930). Bryher played the Manageress & H.D. played Astrid

Author Susan McCabe writes of an unpublished interview from 1979 in which Bryher states that “Film was not my metiér,” and points to the heavy involvement of H.D. and Macpherson when it came to the establishment of The POOL Group and, especially, Close-Up. However, this statement seems to overlook her own intimate involvement with every part of the POOL Group and her own contributions. Whether she felt that her connection to film didn’t last (she became a fiction writer after this period and never delved into the film theory/critical world much after this) and thus it “didn’t count” or she was trying to give her partners more credit really that crucial when you look at her contribution in the end. Her relevance and value to the film community and to film history itself is unquestionable.

While she may not have seen film as the subject in which she excelled or found her “voice,” Close-Up appeared in 1927 and concluded its run in 1933, working its magic by deeply studying topics in film culture that had not been dealt with up to that point. It explored women in the film industry, film technology and technique, race, cinema and class consciousness and other socially relevant film subjects. Furthermore, due to the fact that there were poets, authors and film professionals contributing to the journal, Close-Up benefited from those women and men who elaborated on the experience of the cinema, politics of visual construction, technical aspects of film and simple film reviews. It also underscored the contributions of directors such as Pabst, Eisenstein and Dreyer and highlighted the critical value of Russian filmmaking to the cinematic world. Macpherson served as editor-in-chief, while Bryher was assistant editor. H.D. was a regular journalist/contributor, but all members of the POOL Group wrote for the magazine. Close-Up advertised itself as being the “official guide to better movies” and made demands on the cover, stating “WE WANT BETTER FILMS!!”

Macpherson served as editor-in-chief, while Bryher was assistant editor. H.D. was a regular journalist/contributor, but all members of the POOL Group wrote for the magazine. Close-Up advertised itself as being the “official guide to better movies” and made demands on the cover, stating “WE WANT BETTER FILMS!!”  Close-Up was nothing if not versatile. Just to examine the content of the journal, these are a few of the articles that were published: The Negro Actor and the American Movies by Geraldyn Dismond, The Cinema in the Slums, The Front Rows, There’s No Place Like Home by Dorothy Richardson (another stunningly fascinating woman of the era who wrote these pieces for her regular column Continuous Performance, a feature focused on the experience of watching a film), The Sound Film: A Statement from U.S.S.R. by Sergei Eisenstein, W.I. Pudovkin, and The Independent Cinema Congress by Jean Lenauer. For Bryher, the journal became more a space to express politics and community coordination in the filmic world than one of critical review. The articles that Bryher wrote had titles like How I Would Start a Film Club (1928) or What Shall You Do in the War (1933). The latter of the two articles, written during the onset of WWII, contained the following quote:

Close-Up was nothing if not versatile. Just to examine the content of the journal, these are a few of the articles that were published: The Negro Actor and the American Movies by Geraldyn Dismond, The Cinema in the Slums, The Front Rows, There’s No Place Like Home by Dorothy Richardson (another stunningly fascinating woman of the era who wrote these pieces for her regular column Continuous Performance, a feature focused on the experience of watching a film), The Sound Film: A Statement from U.S.S.R. by Sergei Eisenstein, W.I. Pudovkin, and The Independent Cinema Congress by Jean Lenauer. For Bryher, the journal became more a space to express politics and community coordination in the filmic world than one of critical review. The articles that Bryher wrote had titles like How I Would Start a Film Club (1928) or What Shall You Do in the War (1933). The latter of the two articles, written during the onset of WWII, contained the following quote:

Let us decide what we will have. If peace, let us fight for it. And fight for it especially with cinema. By refusing to see films that are merely propaganda for any unjust system. Remember that close co-operation with the United States is needed if we are to preserve peace, and that constant sneers at an unfamiliar way of speech or American slang will not help towards mutual understanding. And above all, in the choice of films to see, remember the many directors, actors and film architects who have been driven out of the German studios and scattered across Europe because they believed in peace and intellectual liberty. (p.309, Close Up 1927-1933: Cinema and Modernism, Edited by James Donald, Anne Friedberg, & Laura Marcus)

After working with Close-Up , Bryher moved on to other creative pursuits, writing several books and continuing to sponsor literary publications and financially support H.D., although their relationship altered considerably over the years and they lived apart from each other after 1946. Bryher died in 1983 in Switzerland, alone and almost forgotten. To this day, Bryher’s importance to the film world and as a woman in film history has remained buried in obscurity. Without Bryher, there would have been no POOL Group, no Close-Up, no Borderline. It is critical to note that it was not merely her finances that made these projects happen. While Bryher may have been the “money (wo)man,” she also backed them with her unending passion for action. Much like Lois Weber’s drive to depict that which she felt was genuinely important through the visual image, Bryher worked endlessly to make certain that the things that she believed in were published and distributed and accessible to readers and viewers in addition to giving the creative people she believed in a chance to produce their work.

Bryher’s contributions to film culture are vast and many. Some of the first examples of advanced critical film theory and discussions of film in its social application were brought up in the pages of POOL publications. Revisiting these articles, they are still relevant to today’s film world. There is something fresh and active and new about this voice that she helped create, a film voice that sang for experimental works and Russian cinema, the glory of sitting in a darkened theater with strangers and the disappointment of the most recent Hollywood fare over foreign works. Why are we not celebrating People of Color in cinema more? Why are women not having stronger roles? These topics that we speak about today in 2014 BEGAN here.

It is this voice that, even many decades later, points out how little some things have changed. It is my humble proposition that we make Bryher more of an important figure for women in cinema. After all, who doesn’t need how to form a film club? Bryher has more to teach, and I think that she always will.

I ask you all, because her question maintains the utmost relevance: What shall you do in the war?

Addendum: Once again, giving a shout-out where it’s due, I highly recommend that you read one of my very favorite professor’s work on this topic, Historical Predictions, Contemporary Predilections: Reading Feminist Theory Close Up by Amelie Hastie. It is AWESOME, and it will give you a much more full study on this fantastic subject. I would highly recommend it. Without Professor Hastie, I would know nothing about Close-Up and I am the better person for it. The book that I have is so marked up & full of notes…It’s well-loved. So I hope you dig this jaunt! The POOL Group and Close-Up are some fascinating stuff!