Friendly Interactions & the Comfort of the BIFAN Community

I generally travel solo. Sometimes other people are too wishy-washy about attending events or committing to things and at some point I just decided that I would make sure that I never missed the things that I wanted to go to. No shade on anyone else, it’s a me thing.

Traipsing around on my own? It’s what I did in LA. But Los Angeles has a melancholic and toxic sense of loneliness, it makes you feel shitty being alone. I thought that I liked being on my own there, watching people and reading alone in bars. But I like the independence I have here in South Korea much more. In LA, everyone is a lone alone. Here, people just happen to go out by themselves. It’s a different feeling.

Meeting new friends at the festival felt great! People-watching in Bucheon is top-tier, lemme tell you. And having dinner and drinks post-films can’t be beat! If it wasn’t for Grace I don’t think I would have had 1/10th as good a time. That girl is a miracle.

I only had one night where things went off the tracks. The night after Grace left I got terribly lost in the pouring rain. I walked around searching for the place we had been hanging out for the last few nights, trying to use Naver maps, photos I took, you name it.

I finally ended up crawling into a bbq restaurant when hunger and the downpour got the best of me and simply huddled over my banchan and meat like a wet rat, dripping and grumpy. I had never experienced rain like that in my life. My umbrella was about as useful as my earrings. But I ordered some beer and soju and started eating kimchi. These three items, by themselves or in some combination, can cure almost any hardship. That is fact.

I proceeded to sit there shaking my head and laughing at myself. I looked at my wet dress, my flattened hair, my miserable state. The fact that my ass was stuck to the rubber stool and made a noise every time I moved because…WET. It was fucking hilarious. I felt like I had been thrown into the deep end of a swimming pool. But I considered this: after the films I had seen that day, did I genuinely care about water? To hell with monsoon season. There was meat, beer, alcohol. I was finally out of the pour. It was a phenomenal night. It doesn’t get better than that.

It has been argued that one of the more unique properties of film as an art form is in its modality; how it functions. In particular, it is the experience of moving image exhibition that sets it apart. The projection of time-based media in a theatrical space shifts the identity of individuals from being separate to communal. When the lights go down, that collection of perfect strangers transmogrifies into The Audience. Anyone who’s been to a movie has felt it. You lose yourself into the sea of spectatorship in that theater and it is glorious! It is why theaters are still important. That magic doesn’t happen at home with Netflix.

For those who go to film festivals like BIFAN, it is an experience that, whether each person is aware of it or not, becomes a central part of the Festival Journey and is instantly heightened. Seeing a film, a viewer is part of The Audience for the duration of that singular work. However, should that same viewer attend a film festival, they become part of something much larger- a community. You become Community Audience. More specifically, you are Festival Audience. You see familiar faces at screenings. Volunteers and staff recognize you and wave, you nod at others you have seen sitting near you…you have shed your skin and are no longer The (singular) Audience, you are Festival Audience.

I felt this hard at BIFAN and I kept thinking: yes, this is why I am here. This is absolutely why I moved to Korea. These people- this community of film lovers- these humans who come to this festival and are so joyful about cinema- that is what I have been searching for.

I felt so welcomed. It was remarkable. One of the BIFAN programmers- Jongsuk Thomas Nam- was so kind to me and invited me to two online events and while I certainly felt awkward and a little fangirlish, I still felt like I belonged. I sang Olivia Newton John’s Xanadu at the BIFAN zoom karaoke with a cadre of folks I had never met. While it certainly would have been better if I had been back at my hotel to sing, I just went ahead and did it sitting at the restaurant I was at (don’t worry it was outside). Soju…helped.

I got a chance to meet Pierce Conran which was great! We had some absolutely fabulous conversations about mutual friends (Hi Doug!), underappreciated UK noir, Westerns and cinema in general. I was just thrilled to get to nerd out. Again- this reinforced that I was in the right place.

Seeing him around the fest and checking in on movie opinions also made me feel right at home- it’s something I love doing, whether or not a friend or colleague and I agree on a film. Seeing a buddy in between screenings and doing the “what did you think? What did you like? What are seeing next?”- is one of my favorite parts of festival-ing. It made me miss Phil Blankenship and Jackie Greed. I always used to do that “check-in” when I saw them at AFI Film Fest.

While I did spend the bulk of BIFAN on my own, these interactions were so joyful and really highlighted how special the Korean film community is and made me even more grateful to have moved here and been able to experience this festival. I experienced no pretension, no weird looks, no looking-down-the-nose simply because I am passionate about my love for cinema and expressive about it.

I felt so happy. BIFAN really made me feel at home.

Then More Movies Happened….

Day Three: Sunday July 12, 2020

The films that I watched this day were:

Blink (Han Ka-ram, 2020) – Korea

Queen of Black Magic (Kimo Stamboel, 2019) – Indonesia

Pelican Blood (Katrin Gebbe, 2019) – Germany

This was a HELLOVA day. I don’t even know where to start.

While Blink had no subtitles, I was able to understand it with the basic Korean that I do know and the rich cinema vocabulary that I possess. I wish I could convey that to the filmmaker and actors since I could even reflect on the performances and the manner in which they engaged with the genre (Science Fiction) and its representation of gender and power structures. It was part of a special aspect of BIFAN called SF8, which is an anthology SciFi series from 8 different directors. Normally I’m not a SciFi person- I’m painfully picky about anything in that area- but Blink was incredible. It hit the right chords for me in the strong woman category, the unusually creative homage to Terminator (but not a rip-off! SO GREAT!!!!) and detective stories (I’m a straight-up sucker for a good head-strong detective, especially a woman detective).

From that I went right into Queen of Black Magic which was A. Great. Horror. Movie. YESSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS.

But if you hate bugs, that movie is not for you! I may return to this and write about it again because it is a remake of an earlier 1981 film which I need to watch. There were frames of that film in the end credits and I was so enthralled by that. As a film preservationist, it did my heart good to see that and I was genuinely giddy at the way this was just such great horror. But like…I should have known it would be fun and utterly watchable. The name for fun and utterly watchable was right next to the writing credit: Joko Anwar.

Here’s the trailer but SERIOUSLY. IF BUGS SQUICK YOU- DO NOT WATCH THIS.

But Sunday’s movie that made me rethink my eyeballs was a German film by a first-time feature filmmaker named Katrin Gebbe. This film, Pelican Blood, ended up winning the Best of Bucheon Award (and deservedly so). I’ve never seen another movie like it. I thought I knew where it was going and then there was a FULL ON NO-HOLDS-BARRED WTF MOMENT where I exclaimed through my face-mask into the theater: “OH. OK. That just happened then.”

I didn’t mean to. But it happened. And it wasn’t like in other films where I’ve wanted to talk back to the screen for…reasons. The power of this film triggered some kind of feeling in me that set my vocal chords going and by the time the words formed on my lips I couldn’t stop and then there we were.

But Pelican Blood is a film that takes no prisoners and doesn’t give a fuck about you. It’s a film that gives zero fucks, in fact. It’s a naked, raw, terrifyingly brilliant piece of film making that looks at motherhood, childhood, darkness, mental health and all kinds of human pain in a truly extraordinary manner.

I LOVED IT.

I feel weird about wanting to see again because it made me so uncomfortable but it’s such an addictive film to watch. I cannot believe a film like that even exists and I can’t wait to see what this woman makes next.

Day Four: Monday July 13, 2020

The films that I watched this day were:

A Witness Out of the Blue (Andrew Fung, 2019) – Hong Kong

Bloody Daisy (Xu Xiangyun, 2019) – China

The Hand (Choi Yun-ho, 2020) – Korea

I love Hong Kong action films. And I love Louis Koo. Might not be everybody’s thing but hey- I’m not a fan of peanut butter and most people are so…to each their own, right?

Bottom line: A Witness Out of the Blue didn’t have to work hard to please me. But I don’t want to damage the film’s credibility either. It’s a truly funny and enjoyable movie!

You can’t tell by the trailer (which makes the film look like a Very Serious Action Movie) but within the folds of this action-packed Hong Kong heist genre pic you will meet a detective who runs a cat shelter, a parrot who is the only witness to the major crime, and a more than generous helping of quirky side-characters and their background stories. If you’re as familiar with Hong Kong and Asian Action Cinema as I am, then you know this to be one of the most delicious aspects of these films. I adored A Witness Out of the Blue and hope you will as well.

Few films I’ve seen in recent years have made me want to just turn on my heel and go RIGHT BACK into the theater and re-watch the same film, but Bloody Daisy was a film I instantly wanted to watch again. Alternating between scenes of pure drama, action and suspense, this film pays homage to some of the best crime film genres that exist. While the chronology of the picture goes from 1999 to modern day, the life changes, relationship fluctuations and character developments make this a highly charged and multi-layered thriller. The grim nihilism of Hong Kong action films of the 80s and 90s, American film noir and the 70s anti-hero buddy cop films were paid beautiful homage in Bloody Daisy. While I am not certain that the writer/director intended this reading, it is what I received from the film, why I loved it so much and a major reason why I would rewatch it. Aside from the fact that it just rules.

My only criticism (and it almost threw the film for me in certain respects): there is a rather uncomfortable tag during the end credits that has a big thank you to all the policemen working in China, giving all their time and their lives. I find this difficult for me to gauge. It’s very heavy-handed. Therefore, it being China in 2020, I feel a little awkward at this credit sequence message. The feeling towards police globally is not exactly positive and for good reason. On the other hand, Bloody Daisy, an incredible movie ABOUT is not a film about bad cops. HOWEVER the end credit praise was a little off-color for me and didn’t service the film well. I just wondered if he was asked to put that on in order to get the film made or…I have no idea. I don’t want to make any assumptions. It’s uncomfortable.

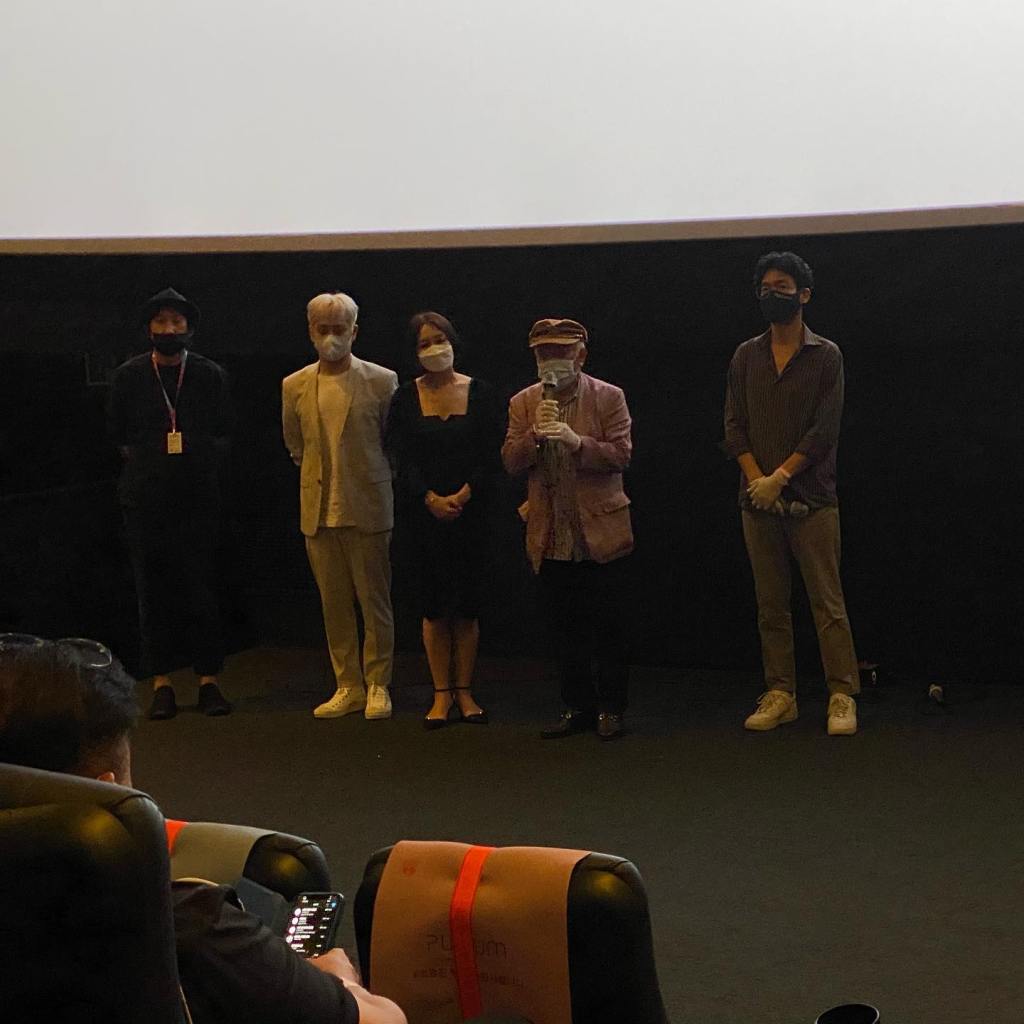

After Bloody Daisy I went and saw The Hand which was a really fun independent Korean horror short film about a hand that comes out of this guy’s toilet and starts killing people. It was super funny in a Evil Dead kind of way. I stayed for the Q&A which (as with the others I went to) was wonderful, even if I didn’t understand the majority of what was said.

Day Five: Tuesday July 14, 2020

The films that I watched this day were:

Sheep Without a Shepard (Sam Quah, 2019) – China

Impetigore (Joko Anwar, 2019) – Indonesia

So Tuesday was another strong day. I mean, hell. They were all strong days. Who am I kidding? There were some films that I loved and some films I only liked, but I enjoyed every single film I saw and I cannot believe what a good time I had at BIFAN.

So let me give you these trailers. If you are bothered by horror, do not watch the second one. Also, neither is TOO spoilery but if you think you will see these films (Impetigore is about to be available for streaming on Shudder) I would advise NOT watching the trailer and just going in blind:

So Sheep Without a Shepard knocked my socks off. Enough so that it’s probably going to get its own individual post since it’s a remake of another film and I want to watch that film and do a compare/contrast. As those who know me are aware, I have done a lot of work in adaptations and remakes and that is an interest for me. In my research on Sheep Without a Shepard, I found that the originating material was actually an Indian movie made in 2013.

So, that post will come! Bottom line, this film won the Audience Award at BIFAN so…it’s a well-loved film and should be seen.

Now on to Impetigore. The first thing you should know is that if you get the streaming channel Shudder or have the ability to rent it FROM a Shudder-connected platform, this face-melting film will be available to stream from July 23rd onwards according to what I have read here.

So the question is…should you? Well, if you like horror films, there is only one answer:

So let’s not disappoint Varla, shall we?

But in all seriousness, Impetigore fucking rules. You know when you’re watching a movie and you’re so deeply involved with it that you absolutely forget that you’re watching a movie?

YEAH. SO Impetigore. That was my experience.

Now, I can’t say that this will happen for male viewers.

This is probably one of the strongest horror films I have ever seen with women as protagonists and central figures. I could probably talk about how much I loved this film for hours based on the dynamism of the women characters and the involvement of puppetry alone but…there is just so. much. to. love. about. this. film. I cannot wait to watch it again when it comes out on Shudder.

Sure, you can certainly see the influence of films like Texas Chainsaw Massacre and more but it’s what Joko Anwar did with the idea of homage that I loved. He translated it into creative intent and unique synthesis not simply repetition.

Day Six: Wednesday July 15, 2020

The films that I watched this day were:

Fallen (Lee Jung-sub, 2020) – Korea

Mrs. Noisy (Amano Chihiro, 2019) – Japan

Taro the Fool (Tatsushi Omori, 2019) – Japan

The Interviewees (Hwang Seungjae, 2020) – Korea

So I could definitely feel the Film Festival Fatigue by Wednesday. But I kept going. Because HELLO. MOVIES TO WATCH.

I started out with Fallen which Grace had told me about. There was a lot to like about it. But it was a little bit messy.

Things I quite enjoyed: the smart way that it mixed the idea of a woman writer, true crime and women’s issues that are very specific to Korea. Fallen examines media exploitation of women, molka, Korean society and its response to queerness, bullying and suicide. It loses the path when it starts to go too deep into the Science Fiction realm. It seemed to be trying to handle too many genres at once which disappointed me because the visuals were strong, the performances great and any 3 or 4 of the things the film had would have worked together but not all 5-6. It just couldn’t hold up under all the multi-genre pressure. Worth watching but just difficult to work with at points.

I loved Mrs Noisy. Ootaka Yoko’s performance alone is extraordinary. It’s hard to talk about the film without saying too much but I definitely have some thoughts. I will try to keep this as vague as possible!

While I may have found myself disappointed with what I saw as a traditional return to domestic values in the third act I don’t believe the film can be chalked up to simple recuperation in that manner. The relationships and discussions are far too complex for it to be that easy.

This sensitive and funny women-centered film examines deeply flawed people and critiques modern parenthood in unique ways. While traditional family values are certainly present, they are not overbearing enough to disregard a film as worthwhile as this. Don’t miss it.

So Taro the Fool. Wow.

I’m not a fan of Harmony Korine or Tod Solondz. I just can’t watch their work. And Lars von Trier…well, I like a few of his films but not many. When I got out of Taro the Fool I thought I completely hated it. I thought it was in the Solondz/Korine school of cinema masochism that drives me absolutely insane. And I still think it might be.

BUT DAMN. I couldn’t get that film out of my head for two days. I just kept. Thinking. About. It. I could not stop thinking about it. There are only a few films that I’ve ever had that experience with: Breaking the Waves (Lars von Trier, 1996), Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971), Germany: Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948) and Come and See (Elem Klimov, 1985).

I am in no way suggesting that Taro the Fool holds a candle to those films; it doesn’t. Whatever Taro the Fool shares with these other films has no name. Taro the Fool wears discomfort and weirdness as a garment, traverses shock, swims through sadness, visits melancholy and returns to revel in awkwardness and anxiety. Sometimes I like films that have all those elements! But used in this fashion…I still can’t decide!

The lady in front of me couldn’t hang. She straight-up walked out at the scene that reminded me a bit of Alejandro Jodorowsky (who I adore). I get that.

But she missed some heartbreaking monologues that made me think: I don’t know if I like this film, but this scene is some of the most amazing film making and most intense shit I’ve ever seen. I fucking love it.

So…Taro is incredibly challenging. I’m still in the “unsure” category. But I sure appreciate it and thank BIFAN for having given me the opportunity to have experienced whatever it was!

My last film of the night was The Interviewees. There was a lot to like about this film since it is clearly based on actual interviews done with people talking about real-life situations in and around employment, happiness, life, death and other day-to-day existential matters and that non-fiction element makes it interesting. But it also weighs down the fact that it is a SciFi film.

Much like Fallen, I think this film might have been trying to do too much and maybe couldn’t decide where it was going. On the other hand, I really enjoyed the performances, the structure and the “twist.”

Day Seven: Thursday July 16, 2020

The films that I watched this day were:

The Kind-Hearted Man (Yamanouchi Daisuke, 2019) – Japan

I ended the festival with a bit of pink film from Japan. It’s definitely not for everyone so I would advise you look into pink film and decide if that is something that you would be interested in before watching this title. That said, it’s a pretty fun horror film with great scares and SFX make up. So some creepy old dude sex scenes, some kinda hot guy sex scenes, some scenes where I was like: “I don’t know if women’s bodies can actually do tha…oh, um, I guess they can. Learn something new everyday,” and some pretty awesome ghost shit.

I’m not going to complain ONE BIT about ending my BIFAN on that note. It was fun as hell!

After the film ended, I went to get some food and joined a bunch of folks for the Zoom online reception. Again, I felt so honored just to be there. People from ALL OVER THE WORLD were on this zoom call. People who are usually at BIFAN. People who were talking about how much they love the festival, the community, how sad they are they had to miss it but they’ll be here next year. Listening to everyone’s updates from Europe, South America, Taiwan…It was truly an incredible experience. My friend Ivy from LA was on the call too (she was one of the only people I knew on the Zoom Karaoke) and it was really nice to see her.

I’ve gone to a lot of after-parties, tons of receptions in my life. I grew up in the industry, on film and TV sets. It’s not that filmmaking or filmmakers in particular make me feel all geeky it’s just that I have a lot of respect for people like the group that were on this closing night zoom call. It was so obvious that it was a huge international collection of human beings who create genre work and REALLY LOVE THE CINEMA and that awed me.

I just love people who love the movies and these people love the movies.

BIFAN seems to bring those people out and…how magical is that?

I closed my evening at this small restaurant where I got a chance to meet a few of the volunteers who had been smiling and waving at me throughout the festival. I seemed to go into their particular theaters more often than others. Sometimes that just happens during a festival- you end up watching movies in only house 3 and 10 for two days!

Some of the BIFAN Heroes!!!

Talking to these young women was so much fun. First of all, it was a really good chance for me to actually speak Korean (I rarely get a chance to speak Korean where I work and live- it’s basically all foreigners/English speakers). And I didn’t do as badly as I thought! I only used Papago when I needed to say really MAJOR things and for a word here and there. Also numbers. I am awful at the number system. Both native and sino-Korean. Don’t judge.

Festivals could not happen without volunteers. And these folks basically don’t even get to see most of the movies! So they were on their way out and I asked them to sit (they weren’t sure at first) and then they did. They asked what movies I preferred (I told them), then we just talked about Korea and why I’m here, how much I love it and random other things.

It was one of the best parts of the festival.

I loved being on the Zooms with the people who made the films for BIFAN.

I loved Zoom Karaoke.

I loved seeing the Q&As and I loved the movies.

But I really really really loved talking to these three women who worked so hard to make sure that everyone stayed safe, healthy and happy at the festival.

That was a tough job. I watched. If you think being a volunteer at a film festival is hard…trying adding the additional aspects of temperature taking for each film, bracelets, ID form filling out, and monitoring all that information when guests go into the theater.

I was so proud just to be able to thank them and talk about movies and have some laughs with them on my last night in town. It was the best way to end my first, and certainly not my last, BIFAN.

And thank you again to everyone who made this festival possible, from festival director and staff to programmers, jury members and other attendees. It was a dream come true. I am still floating 6 feet above the ground in happiness from this experience. BIFAN has made me the most ecstatic film nerd in the north of South Korea. Until next year film friends….