Sitting here, watching Sahara (Zoltan Korda, 1943) on TCM, I was struck by what we are actually missing in today’s cinema and what makes it less than what it used to be: good character actors. See, I think that what created GOOD Hollywood, the Hollywood I love and worship, the films I come back to again and again and again, were not always the Glenn Fords, Rita Hayworths, Bogey & Bacalls, or the like. Nope, not even close. Don’t get me wrong, I have a favorite screen “couple” (Tracy & Hepburn), and I dig all that stuff, but…we had quality character acting even up until the mid-to-late-80’s, I would say. For heaven’s sake, I would (and could) argue that Lee Ving of the band FEAR was an awesome character actor. So actually into the ’90’s. But it was definitely on its way out. Even at that point, good character acting was primarily being shoved onto television and the Silver Screen was being relegated for “more important” content.

From Flashdance & Get Crazy to Clue & The Taking of Beverly Hills, Ving definitely made a place for himself as a character actor

While Wikipedia defines character actors as people who play “a particular type of role rather than the leading ones. Character actor roles can range from bit parts to secondary leads.” My focus is not so much on the ones that play secondary leads. I’m also interested in the supporting cast. Actors that play incredibly important roles but come in and out of a picture and you always recognize them and say, “Hey! It’s THAT guy/gal again!” That’s how I fell in love with Elisha Cook Jr and Walter Brennan. It was how I became enamored of George Kennedy. It’s why Thelma Ritter and Agnes Moorehead will always have a big huge places in my heart, and then, of course, really- how could anyone NOT love Dub Taylor or Ernest Borgnine? It is also how one of my absolute favorites, Henry Silva, became totally etched on my psyche and (I’m guessing) upon Jim Jarmusch’s too. When Silva appeared in Ghost Dog(1999) he appeared alongside a few other equally well-known character actors. In doing so, he was so self-referential as a well-known character actor that his character actor “ness” seemed to be the gag! And it was a good one! Well done, Mr. Jarmusch!

The reality is this: back when men were men and women wore Edith Head, the nutritional supplement of the cinema was your character actors. It was what nourished your films, not relegated them to the “Indie” category. Taking out your vegetables and just leaving the meat gives you an unsupported filmic narrative. Additionally, by taking out those ingredients, you also remove the familiar thread that runs through a multitude of genres, eras, and even media. Directors like Jim Jarmusch and the Coen brothers are outstanding in their ability to utilize character actors in the traditional sense. They flesh them out, give them purpose, sometimes simply within a few scenes and then…they are gone. These characters either disappear completely, or they simply fade into the tapestry of the storyline. But they are not there to be the focus, they just serve as support beams. However, even if these actors quickly disappear, in the next movie? They are used again. And the familiarity of That Guy/That Gal is there! And you know them from a Jarmusch or Coen brothers movie, specifically. However, there are not many filmmakers working like that today, and the films made by these filmmakers seem to have been relegated to a status that is not the same as every other film being released. They do not get the same production or distribution possibilities, they do not get the same publicity, and they simply do not get the same treatment. They never have. They have always been within the categorization of “indie” films. And if I wanted to stretch this out a bit further, I could include other directors who do the same thing. Spike Lee’s early work (like Jarmusch and the Coens’) was considered to be a catalyst of the Independendent Cinema movement, and he also used amazing character actors like Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Danny Aiello, and he practically launched John Turturro’s career. The difference between Spike Lee’s work and the other two directors mentioned above (even though all three men shared actors over the years like Steve Buscemi and John Turturro) is that Spike Lee got “successful” first. That success gave him the ability to put a great deal more money into his pictures and have the meat and potatoes all the time. Not that Jarmusch or the Coens minded, artistically. From what I can tell, they were like good cinema parents. They wanted to make damn sure that we had a full meal with every food group represented on the plate, and were willing to take a few risks and minor setbacks for that. Please do not misunderstand me- I am not calling Spike Lee a sellout. If you ask me, you cannot get a more well-balanced meal than Clockers (1995). But for some reason, he was able to get funding and go somewhere with his work that these guys were not. I find that interesting. Especially since they all were based upon the idea of using character acting as the backbone of their films. Looking at the Independent Cinema Movement of the ’90’s, they used the same character actors for very different reasons than Hollywood did, back in the day. We can look at these films retroactively and say, “Wow! How marvelous! Look at Steve Buscemi in Jarmusch’s Mystery Train!

Only a few years later he would be helping the Coen brothers get much bigger with Lebowski!”

“Phone’s ringing, dude,”- Steve Buscemi’s character of Donny in the Coen Bros’ film The Big Lebowski (1998)

Or you can look at the fact that Jarmusch has used Spike Lee’s brother Cinque in multiple films. Or that Turturro has been bouncing back and forth between the Coens and Lee for years now, doing movies for both. Unlike the studio days, these filmmakers were using each other’s talent out of necessity. The main concept of independent filmmaking was “independent,” also translating to “severe lack of funds.” They had to work with what they got, including how much they could pay people. This meant You Use The People You Know.

Thus, the shared casts between these filmmakers had just as much to do with the budgetary restrictions as it did with their creative choices.

Interestingly enough, it led to a very heavy reliance on casts that were chock full of character actors that served as a kind of connective tissue between their films and their compatriots’. It’s depressing to me that the last time that this kind of narrative and consistent cinematic thickness could be witnessed was within the “Indies.” That was a long time ago. I firmly believe that one of the reasons that so many films today are lacking in depth, plot, and any kind of genuine entertainment value is due to the lack of character actors, be them comedic or dramatic. If you stop to think about it, a good character actor can play to any genre. They might get type-cast, and generally be known for one thing (like Walter Brennan and the Western), but the greatest asset a character actor can have is exactly what a character actor is known for: ELASTICITY in performance. My favorite players have had exactly that, and I miss it like hell. I go to movies now, and it’s almost like going to a park made completely out of cement and iron. I look for the trees, the flowers, the things that make me want to stay at the park, hang out, read a book in the sunshine, and there is simply nothing there. To give you an idea of what is missing, aside from my discussion of the Indie Film Movement, I would like to give you a couple of Character Actor Studies. By briefly looking at the careers of some of these early performers and their works, it should become transparent that when we sit down for a lovely 7-course meal at the Silver Screen these days, all we seem to be getting served is the steak, and that ain’t worth the money being paid! LET’S HEAR IT FOR THE BOY(S)! In the world of character acting, there is a great deal more attention paid to the men and there are, indeed, many more well-known and recognizable male character actors. There are many female character actors, but unless you consistently watch older films, they seemed to have mostly gone into the world of television during their later years, while the men continued to shine on the big screen (as well as the smaller one). But this is Tinseltown after all, and unfortunately that is the traditional unfair gender dynamic that was set up back when the Industry began. That said, it has no bearing on how insanely talented these three men are, and how, without them, Hollywood would not be what it is today. And if anyone was curious, I would be willing to swear to that on a stack of whatever holy book you prefer. I honestly believe that without the help of Elisha Cook Jr., Walter Brennan, and George Kennedy our films would be suffering from severe anemia. Walter Brennan Best known for his work in Westerns, Walter Brennan was actually a great deal younger than most of the parts that he played. Due to the fact that he was always working, he was also always recognizable and ultra familiar. He was nominated for 4 Academy Awards, and won three of them. His performances as an “old timer” from whatever era the film was supposed to be set in, generally worked to his advantage. He played grumpy old men or preachers (Sergeant York, 1941),

eccentric historical figures (The Westerner, 1940) and innumerable men named “cap/cappy” or “pop” or “gramps” or “grandpa.” The figure that Brennan cut was the congenial older trailhand or the corner store owner in the Western town. Shift the narrative to a sea drama, and Brennan was the sea-weary captain. One more time and he was a prospector. In all of these cases, the same things stuck out: his voice, his facial expressions, and, especially, the attitude that he had to the other actors that were within his scenes. While his acting was strong and individualistic enough to have warranted him award nominations, he positioned himself in such a way that it deferred to the star without losing any of his own strength as an actor. Indeed, Brennan essentially invented the character that has been parodied in so many different films, cartoons, and other media objects. While his voice is generally what people use for the imitation (it is one-of-a-kind), his multiplicity of characters created an iconic figure to repeat and have within various genres. People know who Walter Brennan is, even if they don’t know who Walter Brennan is. For example, if one were to describe Stumpy, his character in Rio Bravo (1959), a person would know exactly of whom were speaking.

All we would have to say was that he was the older cooky sheriff chewing tobacco or smoking a cigar, with a loud laugh and a cracking voice and a bad case of messed up teeth. He likes an occasional drink and was essentially not very useful yet considered absolutely indispensable to the main character (in this case, John Wayne) of the film. Dollars to donuts, anyone you talk to would conjure up Walter Brennan. He made that much of an impression upon film and media culture. Elisha Cook Jr.

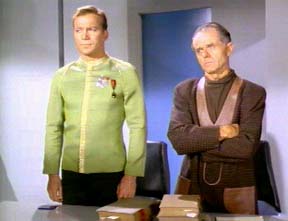

Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and Samuel T. Cogley (Elisha Cook, Jr-credited as Elisha Cook, however) in Star Trek episode “Court Martial” (1967)

Elisha Cook Jr.’s resume reads like film and television history. He played characters that were as varied as gangsters, doormen and the severely mentally disabled. He was in everything (and I honestly do mean everything- he is one of the most visually recognizable character actors ever)  from The Maltese Falcon (1941), Don’t Bother to Knock (1953) and The Killing (1956)

from The Maltese Falcon (1941), Don’t Bother to Knock (1953) and The Killing (1956)

to Shane (1953), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), and Carny (1980). His tv movie appearances are countless (among them Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot-1979, and the Richard Matheson-penned The Night Stalker-1972), and his television appearances weren’t half bad either- Star Trek (1967), S.W.A.T. (1975), Quincy, M.E. (1977, 2 episodes), Magnum, P.I. (1981-1988, 12 episodes) and of course ALF (1988). Elisha Cook Jr. was, clearly, a character acting force to be reckoned with. In my world, if he pops up in a film or tv show that I’m watching, that automatically makes it better. While that may seem like an exceptionally fannish comment (and I’ll admit- it is, but only slightly), I can back up why I think it will be better. When a certain director and/or casting director cast Cook , they were, similar to Walter Brennan-selection, seeking out a certain flavor for the piece. But the special thing about Elisha Cook, Jr (and the way that he differs from Brennan) was that his acting capacity was so wide. While he was certainly selected for that deer-in-the-headlights facial innocence that he had perfected (even in criminal roles), Cook had a complicated and layered innocence, making the film or TV show that much more intense. Elisha Cook, Jr. garnered empathy and sympathy in ways that most actors never could, simply using his eyes, facial features, and small stature. No matter what role he played or how evil the character was meant to be, one always sided with Elisha Cook, Jr. It was a unique talent that he had by playing with his visual aesthetic in tandem with his vocal intonations. In short, he was a great actor. While there are many roles that he has played throughout his career, my favorite has to be Harry Jones in The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946).

Playing small-time hood Harry Jones in The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946), I DARE you not to be moved by his pathos.

In all honesty, the look that he gives the other fella playing the gangster in one of the darker scenes in the film just breaks my heart. That may have been the film that made me an Elisha Cook Jr.-addict. While there were many other actors of his same height and general physicality who played similar roles, only Cook had the kind of talent it takes to bring affection to hoodlums and hen-pecked husbands alike. Unlike Walter Brennan who is primarily recognized based upon his singular vocalizations, Cook is a character actor that is familiar based upon his aesthetics and his characters’ ability to aggregate sympathy. George Kennedy I’ve accepted the fact that many people don’t watch older movies anymore. My friends and associates do, but the outside world-at-large? Not very often. However, there is a very decent proportion of those people who know who George Kennedy is. All you have to do is mention Cool Hand Luke (Stuart Rosenberg, 1967). Just ask about this scene:

In a film chock full of amazing talent, how is it that we remember George Kennedy almost as well as we remember Paul Newman? Harry Dean Stanton is in that movie, as is Dennis Hopper. Those are names that folks would recognize. However, George Kennedy’s character strength is what made him so recognizable. Where Brennan was practically genre-specific and most definitely recognizable by voice and Elisha Cook Jr. had a face and persona that could break a thousand hearts and inspire love for even the lowdown dirty no-gooder characters, Kennedy’s forcefulness and bold demeanor gave him significance. Kennedy was masculine, tough as nails and super badass and many of his roles reflected those things. Like many other character actors, Kennedy found much of his career in television. His roles in Have Gun, Will Travel (7 episodes, 1960-63), The Asphalt Jungle (3 episodes, 1961), Bonanza (2 episodes, 1961-64), and McHale’s Navy (2 episodes, 1963-63) only increased his popularity and solidified his “larger than life” persona. He even had his own television show, Sarge, which featured Kennedy as a cop-turned-priest who just can’t stop solving those crimes! Sarge brought big names out too- Vic Morrow, Martin Sheen, Leslie Nielsen (who he would later work with on the Naked Gun films) as co-stars and folks like John Badham and Richard Donner to direct.

Within Kennedy’s “character presence,” there was one feature that he carried on to almost every role he played: perseverance. While in some films it could be labeled as “stubbornness” or “hard-headedness” that was part of the Kennedy charm. It could make a character heroic (Airport, 1970)

playing Joe Patroni, the determined airline mechanic who does things his own way in order to try to save the day in Airport (George Seaton, 1970)

or brutal (Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, 1974).

playing the nasty Red Leary, determined to get his share (and way) of everything no matter what (Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, Michael Cimino, 1974)

It could catalyze a sense of martyrdom (Delta Force, 1984) or it could cause tunnel-visioned determination that doesn’t pan out so well (Lonely are the Brave, 1962). In addition to this, Kennedy’s physicality is a very distinctive part of his oeuvre. It is so much a part of his “characterization” that he played four roles in four different shows/films where the character’s descriptive nickname was “Big” (ie “Big” Jim or “Big” Buck). Where Brennan went with the voice and Cook entangled facial expression with physicality, Kennedy’s impressive physical stature made him a perfect candidate for characters needing a tough persona and thus will be remembered as such. FEMALE TROUBLE Before we discuss the ladies, I would ask that you slide on over to Celluloid Slammer and check out their little ditty on character actresses, because truly…it’s fantastic. In the world of character acting, the men get a lot of love, but the women need some lovin’ too, and that post made me happy. Now that you’ve done that, shall we begin? Thelma Ritter

The exquisite Thelma Ritter was probably in a very healthy chunk of the films that you were forced to watch in film school. Whether you liked them (or her, for that matter) is really none of my business, but the fact that a such a mousy-seeming woman could make such a significant place for herself in some of the best films that Hollywood made is still a very commendable feat. Ritter is another actress that you know her face, but you can’t remember from where or why. That is her gift. The first reason is that she’s in darn near everything, and they’re all pretty decently popular titles. The other reason is that Thelma Ritter is the kind of character actress that doesn’t impose herself on the film or the narrative. She almost becomes as crucial an element to the story as the storyline itself: you couldn’t imagine the film without her, and yet she is the least imposing figure you could think of. While she generally plays nurses, housekeepers or caretakers in general, she has also been cast in several roles that document her dramatic abilities without question. Her roll as the poor police informant Moe Williams in Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953) is nothing short of brilliant. Both dramatically strong and crushingly heart-breaking, Ritter plays Moe’s part as real as they come, up until the very last moment. To me, that is her most memorable performance and also my favorite.

However, Ritter’s work is extensive and each role, no matter how seemingly insignificant, is as unforgettable as she is, the sign of a good character actress. Unlike many character actresses, her career was almost exclusively in film. In general, most character actors/actresses have healthy resumes on both the little and the big screen. However, Thelma Ritter’s work existed almost entirely on the big screen, mostly due to the fact that she was unendingly usable. She fit into almost any context and any genre and there seemed to be roles cut out just for her. She invented an archetype, really (“the Thelma Ritter type”). And her list of films is GOOD GRAVY astounding. While Sam Fuller’s film may have only gained respectability within recent years, she rocked it as Birdie in All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), did a turn as Maude Young in Jean Negulesco’s Titanic (1953), and continued on to pieces like Pillow Talk (Michael Gordon, 1959) and The Misfits (John Huston, 1961). Now I’m not saying the lady didn’t do television- she most certainly did (there’s an “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” that I’m dying to get my hands on!), but the cinematic roles that she played helped to carve out and create a character type. In my mind, Thelma Ritter is somewhat of a legend. She can go from nosy neighbor to helpful housekeeper in the span of 1 film, yet always maintain that certain something. Her Ritter-ness has yet to be matched. I have not seen another actress who can carry that serenity on her face or the same playfulness or the grim determination, at times within the same film. My take on her is that, through being a character actress, she was able to use her wide variety of skills to dance through an industry that tried to pigeon-hole you into being one thing. I think she truly enjoyed her work and the variety of roles it gave her. I certainly love watching her. Agnes Moorehead While many people have grown up knowing her simply as Samantha’s mother Endora, Agnes Moorehead had a very brilliant career that started way before her turn as the technicolor witch on Bewitched.  Though not conventionally attractive, Moorehead certainly had the power to be so. She played a multitude of characters over her career, ranging from her regular appearances in Orson Welles’ films to the aforementioned television series. I was pleasantly surprised to catch a lovely little film the other day called Mrs. Parkington (Tay Garnett, 1956), starring Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon. What I found to be the real kicker was that Agnes Moorehead, playing the Baroness Aspasia Conti in the film, is actually constructed as a beautiful and sexualized character. Played in opposition to the protagonist, she is regal and beautiful but aging, and discusses these issues in such a way that is unusual and terribly unique. The reality of the situation is that the way that Moorehead is dressed and made-up, she is every bit as attractive as the lead, but that doesn’t gel with the narrative (nor does it gel with the characters that Moorehead plays on a continual basis), so she does become a secondary figure. But she is still seen as being a sexually attractive female, something that Moorehead did not get to do too often.

Though not conventionally attractive, Moorehead certainly had the power to be so. She played a multitude of characters over her career, ranging from her regular appearances in Orson Welles’ films to the aforementioned television series. I was pleasantly surprised to catch a lovely little film the other day called Mrs. Parkington (Tay Garnett, 1956), starring Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon. What I found to be the real kicker was that Agnes Moorehead, playing the Baroness Aspasia Conti in the film, is actually constructed as a beautiful and sexualized character. Played in opposition to the protagonist, she is regal and beautiful but aging, and discusses these issues in such a way that is unusual and terribly unique. The reality of the situation is that the way that Moorehead is dressed and made-up, she is every bit as attractive as the lead, but that doesn’t gel with the narrative (nor does it gel with the characters that Moorehead plays on a continual basis), so she does become a secondary figure. But she is still seen as being a sexually attractive female, something that Moorehead did not get to do too often.

Moorehead was, many times, part of the Old Maid/Crochety Woman character actress circuit. These were the female characters in films who, according to much recent film theory, are the flimsily disguised lesbian characters. They played the matronly aunts, the stern heads of orphanages or prisons, or other spinster-esque figures that had no romantic implications…at least not with men. Indeed, there were many allegations that Agnes herself was gay, but those went unproven. However, many characters that Moorehead played fall into a type that has been considered a little “less than hetero.” Her relationship with the Mercury Theater and thus Orson Welles brought her some amazing roles and showcased the strength of her performative skills. Moorehead’s ability to take charge of a scene just within a few lines can be seen in films such as Citizen Kane (1941) and Jane Eyre (1943). But if you truly want to see a great performance, get your paws on a film Welles and the Mercury Theater gang did called Journey Into Fear (1943). Not unlike my Thelma Ritter/Pickup on South Street reasoning, my favorite Agnes Moorehead film roles are the ones that showcase a different image than her usual one and underscore her talents. Therefore I feel that Mrs. Parkington is a really fine film for exploring a different side of the Moorehead persona as far as sexuality is concerned. However, my real favorite is Journey Into Fear. While her role as Mrs. Mathews has some of the familiar qualities that she carries through her career (she plays the prototypical bullying-wife role), she also gets to shine with a few truly brilliant comedic turns. Part of that is the writing and the chemistry she clearly shares with the other actors, but a good portion of that is all her own. Later on, that comedy is quite visible in Bewitched (which she was on from 1964 to 1972) but up until then, her comedy stylings were somewhat more concealed. A great radio-star and a fine actress, Moorehead, like Ritter, created a character standard. While Ritter’s was the kind and dependable housekeeper/neighbor/nurse, Moorehead virtually defined the matronly female figure. Her physicality and stern features in addition to her unwaveringly strong and full voice cut a striking figure on the cinematic canvas. I have always considered Moorehead to be more of the George Kennedy-type. You knew what you were getting, and what you wanted to use her for. Unfortunately, after seeing Mrs. Parkington, I realized how wrong I was. She got type-cast, an unfortunate side effect of being a character actress. I suppose if you are good at something, that can tend to happen. It is an unfortunate occurance, however, seeing as she did have other skills that got explored (to an extent) earlier on in her career. I do wonder sometimes what it would’ve been like to see her play something perhaps a bit less austere. But then I watch her interact with Eleanor Parker in Caged(John Cromwell, 1950) and…well, I just love it so much I guess I accept things how they are. Father…er…Hollywood knows best?

While definitely a more sympathetic character than the women prison guards, Moorehead’s turn as Ruth Benton in Caged doesn’t stray much from her typography of roles given.

Mercedes McCambridge Not every character actress has been pleased about the roles that they have played or perhaps their character actress status, regardless of how well they completed the task. Mercedes McCambridge is one of those figures. Her lot in Hollywood was certainly much more tragic and difficult that the above two ladies and I have definitely heard people refer to her as a “cult” figure in a slightly condescending manner, which truly breaks my heart. Indeed, McCambridge herself said, “One of the most destructive things in my life was the kind of parts I played in pictures. I studied Shakespeare and the classics, and I end up shooting Joan Crawford and killing a horse that Elizabeth Taylor was in love with. I’m serious. I played the worst harridans, the most hard-bitten women, the absolute heavies, and it just about did me in.”

People can call Johnny Guitar a “cult classic” all they want. I’ll just call it one of my favorites that I can put on, oh, just about anytime. A chick Western by Nick Ray- what’s not to love??

Well, Mercedes, here is the problem- you play the heavy so damn well! Being a fan of noir, I’ve seen a good amount of mean and bitter characters in the movies. But Old Hollywood rarely gave women a chance to explore that area. We were allowed to do the manipulative and vindictive femme fatale (and some of them could get pretty damn mean) but for the most part, women didn’t get to be rough and hard. I don’t know. Perhaps it was some kind of Delicate Flower Syndrome in tandem with the desperate fear that we actually have the capacity to be rough, hard-bitten bitches when we wanna be. Guess I can’t blame Hollywood too much. In any case, we got that freedom later, so can’t complain too much. But Mercedes did it early and she did it with style, even if those weren’t the roles that she wanted to play. McCambridge actually had a great deal in common with Agnes Moorehead. Like Moorehead, she was extremely successful in radio and her career there flourished for years right alongside her film and television work. Not only that, but she too was a member of the Mercury Theater, thus getting in with Mr. Welles which most likely led to her legendary (but uncredited) role as the androgynous gang leader in Touch of Evil (1958).

Mercedes as the gang leader who had a bad case of scopophilia when it came to Janet Leigh getting raped…

Previous to that role, of course, she was plenty active. She had developed a very clear and defined position within Hollywood. In fact, she won an Academy Award her very first time out of the gate! Her screen debut was in Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men (1949), and she nabbed a Best Supporting Actress Award. Not too shabby. Throughout her career she worked intermittently on television, film and radio. She also continued to do work on the stage, something that many character actors/actresses pursued. While people tend to be more aware of her roles in films such as Giant (George Stevens, 1956) or Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray, 1954), McCambridge managed to demonstrate her theatrical ability in pieces such as Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). The Tennessee Williams/Gore Vidal-penned script alongside the stellar cast of primarily stage-trained actors really gave her a good launchpad to create the character of Mrs. Grace Holly. While this role may not have been the best example of female strength (I’m not certain you can depend on Tennessee Williams to give you particularly positive examples of either gender-to be honest, he’s a fairly equal opportunity misanthrope), McCambridge manages to imbue the character with at least a modicum of sympathetic attributes, which is a feat. While her presence in television and film was powerfully based within the Western genre, doing everything from Cimarron (Anthony Mann, 1960) and Run Home Slow (Ted Brenner, 1965) to multiple episodes of shows like Bonanza (1962-1970) and Rawhide (1959-1965), her most famous role (for the majority of the populace) is in a film where she never ever appears: The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973). CAUTION: CLIP NSFW, LANGUAGE & CONTENT IS…HORROR FILM.

The flexibility of a character actor seemed to provide them with things that the Big Stars don’t get. My grandmother was afforded a successful career in television, film and an extraordinarily active life on the stage. She was another woman who began on the radio, and spent many successful years there as well. Some of my fondest memories involve her singing or reading to me (yeah- ain’t nothin’ like a highly-trained Shakespearean actress reading you stories to put you to bed as a kid- natch!). Oh, and she made damn fine cous cous. But I digress…However, my digression proves the other flexibility: she had time to put into a thriving family life. Many of the bigger stars had to forgo this aspect and their children and grandchildren suffered the consequences. My mother and uncle did not. Neither did my brother and I. My grandmother was working all the way up until the day she had a stroke in her 80’s, but (and I would have to ask my mom/uncle about this) I don’t think that she ever felt the work/family strain as massively as the Big Hollywood Talent. Interesting. I don’t think she was unusual in this, either. Thelma Ritter took a few years off of her established stage career to raise her kids…Does it go with the territory?

My grandmother in Norman Jewison’s The Cincinatti Kid (1965) with Tuesday Weld, Steve McQueen and Karl Swenson

Character actors are unique in a multitude of different ways. Their lives and careers are different, they have different trajectories, and different methodologies. Personally, I find them more exciting than your average Big Star, due to the fact that they have such range and depth in roles. Even if a character actor is known for something (like Crispin Glover is known for being a bit “off”), I still enjoy each different permutation of that something, even if the actor tends to stick to what he/she is known for. I will fully admit to being a character actor junkie, and I don’t need or want any help for it. In fact, the more movies I watch, the worse the disease becomes! Oh, more noir…Yep, add Charles McGraw to that list. Oh, more NYC cop/gangster/exploitation flicks? Joe Spinell, you are right there, baby. I began writing this before I started really investigating my grandmother’s career as a character actress, mostly because I felt that, as media scholars/film or television lovers/people of the modern age, we should not only know who these people are, but appreciate what they have done for us. I would’ve loved to have written on more people and written more about the people I did write about, but short bits seem to work. Character actors help us in many ways. If we didn’t have the character actors in cinema, there would be no reality to a film. If you sit and think about it, the character actors in any picture are what actually ground it, even in a fantasy or sci-fi film. Who is the character that always points out the common sense option or helps out in a moment of crisis? Many times, your character actor. They are the string to that filmic balloon, and are desperately necessary. We just don’t always recognize it, as they have always served as the unsung heroes of cinema, in my eyes. Well, today I sing for them. Loud and clear. Thanks, guys. We appreciate you. Nameless to many, but recognizable by face or voice to millions, you are loved. Thank you for your hard work. Keep it up! We’ll be watching!